VIII. Hopeton

A letter to bro David: July 1868

Life and Letters: 1924

...When we got down to the hot San Joaquin plain at Snelling the grain fields were nearly ready for the reaper, and we began to inquire for a job to replenish our remaining stock of money which was now very small, though we had not spent much; the grand royal trip of more than a month in the Yosemite region having cost us only about three dollars each. At our last camp, in a bed of cobble-stones on the Merced River bottom, Mr. Chilwell was more and more eagerly hungering for meat. He tried to shoot one of the jack-rabbits cantering around us, but was unable to hit any of them. I told him, when he begged me to take the gun, that I would shoot one for him if he would drive it up to the camp. He ran and shooed and threw cobble-stones without getting any of them up within shooting distance as I took good care to warn the poor beasts by making myself and the gun conspicuous. At last discovering the humor of the thing he shouted: "I say, Scottie, this makes me think of a picture I once saw in Punch--game-keepers driving partridges to be shot by a simpleton Cockney."

Then one of those curious burrowing owls alighted on the top of a fencepost beside us, and I said, "If you are so hungry for flesh why don't you shoot one of those owls?" "Howls," he said in disgust, "are only vermin." I argued that that was mere prejudice and custom, and that if stewed in a pot it would make good soup, and the flesh, too, that he hungered for, might also be found to be fairly good, but that if he didn't care for it, I didn't.

I finally pictured the flavor of the soup so temptingly that with watering lips he consented to try it, and the poor owl was shot. When he came to dressitthe pitiful little red carcass seemed so worthless a morsel that he was tempted to throw it away, but I said, "No; now that you have it ready for the pot, boil it and at least enjoy the soup." So it was boiled in the teapot and bravely devoured, though he insisted that he did not like the flavor of either the soup or the meat. He charged me, saying: "Now, Scottie, if you go to England with me to see my folks, after our fortunes are made, don't you tell them as 'ow we 'ad a howl for supper." He was always trying to persuade me to go to England with him.

Next day we got a job in a harvest field at Hopeton and were seated at a table once more. Mr. Chilwell never tired of describing the meanness and misery of so pure a vegetable diet as was ours on the Yosemite trip. "Just think of it," said he, "we lived a whole month on flour and water!" He ate so many hot biscuits at that table, and so much beans and boiled pork, that he was sick for three or four days afterwards, a trick the despised Yosemite diet never played him.

This Yosemite trip only made me hungry for another far longer and farther reaching, and I determined to set out again as soon as I had earned little money to get near views of the mountains in all their snowy grandeur, and study the wonderful forests, the noblest of their kind I had ever seen--sugar pines eight and nine feet in diameter, with cones nearly two feet long, silver furs more than two hundred feet in height, Douglas spruce and libocedrus, and the kingly Sequoias.

After the harvest was over Mr. Chilwell left me, but I remained with Mr. Egleston several months to break mustang horses; then ran a ferry boat Merced Falls for travel between Stockton and Mariposa. That same fall made a lot of money sheep-shearing, and after the shearing was over one the sheep-men of the neighborhood, Mr. John Cannel, nicknamed Smoky Jack, begged me to take care of one of his bands of sheep, because the then present shepherd was about to quit. He offered thirty dollars a month a board and assured me that it would be a "foin aisy job."

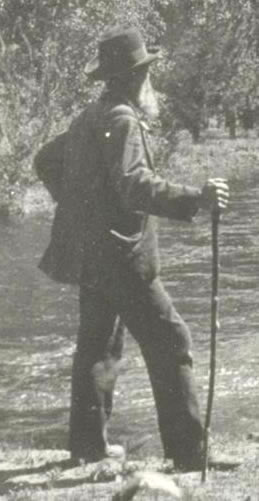

Son of the Wilderness: 1946

...After ten days' stay in the valley they came back to the vicinity of Snelling. Where they found work in the gravest fields of Thomas Eagleson. His fever cooled with mountain winds and delicious crystal water," Muir now enjoyed such health as he had seldom known in his life. Since he needed more money, he was content to remain here for a time. The wide Central Valley stretched for to the north and south between the Coast Range on the west and the sharp, snow-clad Sierra on the east. "They form together with the purple plains and pure sky, a source of exhaustless and unmeasurable happiness from all the fields where I work," he wrote to David. "Farming was a grim, material, debasing pursuit under Father's generalship. But I think much more favorably of it now."